The meeting-discussion organized by Mongolia’s State Great Hural and the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) continued with its second segment, focusing on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and its Committee.

In this part, Hilary Gbedemah—former Chair and member of the UN CEDAW Committee, current IPU expert on the Convention, and Rector of the Ghana Institute of Law—presented on the Convention itself, its Committee, and the Optional Protocol. She explained that the Convention was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1979 and came into force in September 1981 after the 20th ratification. Widely regarded as the principal international women’s rights treaty, the Convention defines all forms of discrimination against women and mandates national measures to eliminate them.

The Convention guarantees women equal political and public participation—such as voting and eligibility for office—as well as equal rights in education, health, and employment. It protects against sexual exploitation and violence, upholds reproductive rights, and recognizes that family roles should align with cultural traditions and human rights standards.

Mongolia ratified the Convention in 1981. States Parties are obligated to incorporate gender equality into their legal systems, repeal discriminatory laws, prohibit such laws in the future, possibly create specialized courts or institutions, and eliminate discrimination in practice. They must also submit national implementation reports to the Committee every four years—Ms. Gbedemah emphasized this obligation.

The independent CEDAW Committee, composed of 23 women’s rights experts from around the world, monitors implementation. Notably, Mongolia was represented by Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary L. Ider, who served as Committee Chair in 1985 and was an expert from 1982–1987.

The Committee reviews national reports, issues recommendations, and under the Optional Protocol (effective from 2000), operates quasi-judicial procedures to handle individual complaints and conducts follow-up reviews based on established benchmarks.

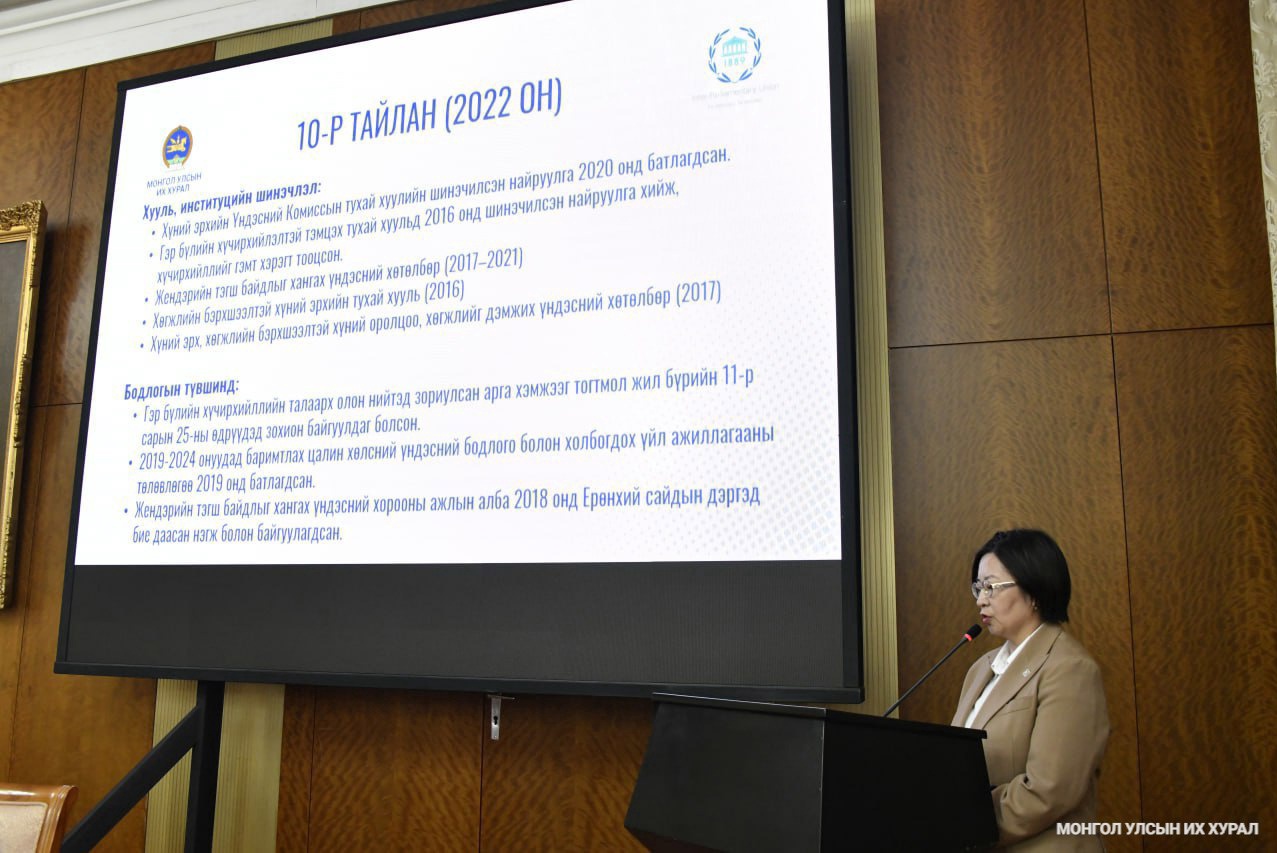

During this session, L. Enkhnasan, Chair of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Policy, presented on Mongolia’s progress in implementing recommendations from its 10th CEDAW report. The government has introduced multiple measures to protect women’s rights, including coordination mechanisms to combat gender-based and domestic violence.

However, she highlighted the need to institutionalize prevention, eliminate violence against women and girls, enforce women’s labor rights, and promote work-life balance.

Since submitting the 10th report, Mongolia has established specialized family courts at district and appellate levels, amended the Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, revised the Social Welfare, Employment Promotion, and Family Support Acts, and is preparing over ten laws concerning accessibility, sign language, etc. In the 2024 election, among 1,341 candidates, 537 were women, 32 were elected, and three serve concurrently as ministers. Due to these gains, Mongolia has risen 34 places in the IPU’s Women in Parliament ranking, now positioned at 96.

Gender-responsive training for instructors and officials has been institutionalized. A multidisciplinary task force was set up under the revised 2024 Child Protection Law to assist child victims of trafficking, establishing standard procedures and shelters. According to the 2025 Global Gender Gap Report, Mongolia climbed 20 spots to rank 65th.

Moving forward, more detailed gender statistics and protection of women’s property rights were emphasized as priorities.

Following L. Enkhnasan’s presentation, participants—including researcher Ts. Munkhtuya and director of the Psychology Sensitivity NGO, Ch. Semjidmaa—asked detailed questions about the implementation of the 2007 126-article work plan, adolescent reproductive health, and received comprehensive responses. The meeting-discussion is ongoing.

Eng

Eng  Монгол

Монгол